On June 2nd, 2019, my husband Chris and I lined up at the starting line of the Trans Am Bike Race. This 4,300 mile race starts in Astoria, Oregon and ends on the opposite coast at Yorktown, Virginia. Yes, it really is a race, although there are no prizes or big crowds to greet the winner at the end. The race is also unsupported, which means there are no support cars, checkpoints, or anything of that nature – each rider must carry everything they’ll need or source it on the road. In 2019 Australian Abdullah Zeinab set a new course record at 16 days, 09 hours, and 56 minutes. The middle of the pack finishes in about 25 days, give or take, but we decided we would be happy with anything under 30 days.

Spoiler alert: we never made it to the finish line.

Every racer has their own motivations for attempting such a crazy feat. My journey has been about living life to the fullest despite health challenges, and proving to myself that I’m capable of more than I realize. Chris just really likes “Type 2” fun, which is the type of fun that comes along with adventures that are challenging and maybe even a little scary. They aren’t always enjoyable in the moment, but leave you with an overwhelming sense of satisfaction and happiness later on after they are over. He admits that he is not nearly as motivated to embark on these sorts of adventures if he doesn’t have someone to share the experience with, and thus he is willing to stick with me despite often embarking on these adventures while not feeling my best and not at peak physical capability. [Chris: Type 2 fun is also known as ‘retrospective’ fun; the best part is looking back on the memories you create, but for me that only works if I have someone else who was there to reminisce about it later.]

Chris and I met while working as Center Directors at Appalachia Service Project, which is a job that is overflowing with Type 2 fun. The foundation of our marriage is tackling goals together that are challenging but rewarding. Random fun fact: we got engaged at an ASP facility in Chavies, Kentucky – an extremely small town that just happens to be right on the TransAmerica Trail!

I’d like to tell you about my health journey, because I’d like to think that this is a worthy story with a moral at the end. I do not intend in any way, shape, or form to leave you with the impression that I’m asking for pity. This is not a sob story. I do not feel that my life has been more challenging than the average person’s. I also promise that my daily race recaps will be enjoyable and not entirely filled with sorrow and negativity. Stick with me here for a bit, please.

Starting in my late teens I came down with mysterious spells of extreme exhaustion every year, sometimes multiple times a year. They were often initially triggered by the common cold, but would linger for months and leave me somewhat incapable of working or going to school. The only thing doctors could ever find in my blood work was that I’d have elevated Epstein Barr Virus antibodies during these episodes; otherwise I seemed like a completely healthy young adult. The term “chronic fatigue syndrome” was thrown around, but in 2009 a doctor advised me to keep the diagnosis and any mention of my symptoms off of my health record because most physicians would not take me seriously if they knew about it.

When Chris and I moved from our respective Midwestern hometowns out to Seattle, I did exactly as this doctor advised and tried to hide my health challenges from everyone. This made “adulting” really difficult. I bounced from job to job with periods of unemployment because I did not ask for accommodations when I was feeling ill, and I had a hard time making friends because I didn’t feel that I could be authentic with people. I lacked confidence and set the bar for my life pretty low. It’s not that I didn’t have any goals or dreams, it’s just that I didn’t think I was capable of achieving any of them. That’s where cycling came in to save me.

I started off my cycling career as an occasional commuter, and had no intention of turning it into a life passion. I simply hated sitting in car traffic. I wasn’t very athletic growing up, and didn’t see any point in trying if it wasn’t something I’d ever be good at. In 2013, our car was totaled and we decided we didn’t want to buy another one. Instead, we started using our bikes to get out of the city on the weekends, daring ourselves to go further and further. I was out of shape and comically slow, but loved the feeling of pride I experienced after tackling a new distance.

After a few years, we accidentally became good at it. The thing is, you can actually be successful at endurance sports without being a very strong athlete in the traditional sense. You just have to be resourceful and stubborn as hell. After all my experiences pushing through illness, I was really good at suffering and tough as nails. It was a way to take a heartbreaking, frustrating thing in my life and turn it into a positive. As a bonus, I found that a strong base of endurance fitness helped me to recover from ‘flare ups’ faster. So I took to cycling like nothing else I have ever done, and started racking up crazy mileage.

Plus, it was a ton of fun!

Chris and I had no idea that things like bikepacking or ultra cycling even existed, so we called ourselves the most hardcore leisure cyclists ever. We were already habitually light travelers, so we tended to pack nearly nothing on our overnight cycling tours. Even then, we already had a distaste for anything that might make us go slower.

We also tended to fail up — a lot. Like that time when we decided to ride the Iron Horse trail on a three day trip through the Cascade mountains in Washington, without realizing that our tires were completely and utterly worn out. (Are you supposed to change those? Is that a thing people do?) It resulted in so many flats that we went through all our supplies, and since we never brought camping gear with us (TOO HEAVY) we were determined to hike the 20 miles to the next motel. Thankfully I found a small spot with cell reception and hired the Roslyn Party Bus to come save us.

We were introduced to the concept of unsupported ultracycling in Spring of 2017. I had quit my job (again) and was bed bound with a particularly bad flare up of my mystery illness. For some reason, I was experiencing repeated cycles of flu-like symptoms, covered in hives 24/7, and I also bizarrely became temporarily allergic to almost all food overnight. I still couldn’t get a diagnosis, so I started grasping at straws and thought I might somehow be doing this to myself by riding my bike too much. I convinced myself that perhaps I shouldn’t be attempting to ride my bike long distances anymore. I also questioned whether it was worth it to continue pushing myself to get out there when I was constantly experiencing setbacks and failures. I was tired!

Thankfully, around that time I happened to come across an article talking about the Trans Am Bike Race and accompanying documentary (Inspired to Ride). I instantly knew that this was exactly the sort of oddball thing Chris and I were born to do, and I threw away all thoughts of stopping our cycling. I was going to find a way to enter the race, and I was going to do it as soon as possible while there was even a slight chance I’d be healthy enough to do it. I was not about to put this one off until retirement.

We weren’t sure if I’d be capable of completing the necessary training, or if it would make me more ill. We decided to target the 2019 race in two years, which would give us a buffer if anything went awry during preparations. In the meantime, I’d try harder than I had ever tried before to get a more solid diagnosis and some sort of treatment plan, even if I was just covering symptoms. Surprisingly, the increased amounts of training seemed to have zero negative impact on my energy or frequency of illness, and the first 18 months went REALLY well.

I spent many nights laying in bed wide awake, wondering if it was worth it to go through all this effort when I had so many unknowns surrounding my health. I worried about feeling embarrassed if we failed in our endeavor. I never let it stop us though, and that’s the important thing. We checked all the right training boxes: riding for 24 hours straight, traveling in areas with few services, tackling mountain passes, going outside in inclement weather, taking an 800 mile practice ride, and thoroughly testing all our gear. When I was too unwell to ride I used the time to read ultracycling blogs, plan out our new bikes, and research the race course. I told people that my philosophy was to ‘act as if I’m a Trans Am racer’, even when I wasn’t able to train. I was also simultaneously visiting doctors about 3 times a week and spending hours researching to determine next steps in my quest for a diagnosis. I knew I was too inconsistent to benefit from a cycling coach, but I taught myself the ins and outs of Training Peaks (a training app focused on cycling) to help us make the most efficient use of our limited training time. I cut out all unnecessary distractions from my life and delegated as many tasks as possible so that I could spend all my free time resting and getting extra sleep. We worked smart, and not too hard. When inquiry for the 2019 race opened in October of 2018, Chris and I both felt pretty confident in signing up.

As we entered 2019, however, it became clear that something was really amiss. My ever growing mental toughness was allowing me to push through the pain, but it seemed like all of a sudden my body was completely falling apart. Doctors visits yielded nothing useful, and like usual I was told to continue with my routine. By March, the symptom list was dizzying: relapsing fevers, vertigo, lightheadedness, headaches, muscle aches, excruciating pain in my abdomen and between my sternum, muscle twitching, tremors, vision abnormalities, tinnitus and hearing sensitivity, weakness, nausea, exhaustion, cognitive impairment, anxiety, an enlarged and painful spleen, joint pain, tingling in my extremities, worsening asthma and hives, a sore throat, and the list goes on. Waking up in the morning was at times torturous and it took several hours for me to get out of bed. We were managing about half the training we had planned to do, but made every ride count.

I took most of April off to rest, started working from home full time, and flew out to my parents in Texas for some sunshine. The extended break didn’t do anything to help, so my primary care physician told me that he wanted me to return to my exercise routine, stating that it would be better for my health long term to avoid de-conditioning, even if it was hard. He fully supported the crazy endeavor we were about to embark on. No one was sure what was wrong with me yet, but most doctors were thinking it was something autoimmune.

I’ll be honest, at this point Chris and I were both starting to feel desperate and despondent. We always knew we’d be facing a few extra challenges, but this was WAY more than we had planned for. We talked about scratching several times and both of us “quit” at various points, but it never stuck for longer than a few hours. To me, it seemed against the spirit of the race to quit before even starting, unless you truly had a race ending injury or situation at home that would 100% prevent you from riding. Plus, based on what my doctors were telling me I was worried that this was permanent and that I’d never be well enough to race TABR ever again.

It became pretty clear that we were unlikely to reach our original goal of finishing in less than 30 days, so we amended our goal to 40 days. That’s the maximum amount of time we could spend out on the course before needing to return to our jobs. On days when I was feeling particularly ill, we went out on the trail near our house to see how many miles per hour I could ride when I was going slow enough to manage all my symptoms. We spent a lot of time making ‘worst case scenario’ calculations. What was the minimum speed I could realistically ride while keeping us on pace for our new goal?

Eventually as I became weaker and needed more and more days off training, we started to worry whether I would be capable of riding at all, and whether it would be safe or good for me. We couldn’t stand the thought of not showing up, but we also lamented the thought of putting ourselves through the race if we were certain to fail. Meanwhile, my mom needed to know whether or not to book a ticket to fly out to us so that she could watch our cats while we were gone. Chris and I finally made the decision that our primary goal was to get to Missoula, which was about 1000 miles from the starting line. If we managed to make it there in 9 days, we would know we were on pace to finish the whole 4,300 mile course in under 40 days. We would decide at that point if we thought I was healthy enough to handle the whole thing, but for now we were going to act like we were racers! Some of this would depend on where I was in my symptom cycle when the race began, because my relapsing fevers tended to come on a 10-14 day schedule. If I got lucky, I might be able to enjoy a week of racing before the illness set in again. We told a couple family members and close friends about the plan, but otherwise we acted totally normal.

In a last ditch effort to save the race, we decided to rule out medication problems as a potential source of my new symptoms. Singulair was the most likely culprit, since I had just started it in December. I happened to have two good weeks after removing it, so we thought we had found the culprit and celebrated. After my symptoms returned again, I really started grasping at straws and took myself off EVERYTHING. The antihistamine I was taking (Xyzal) is famous for making people maddeningly itchy when they attempt to withdraw from it, so now not only did I feel really sick but I was also up all night compulsively scratching. I made a big batch of homemade anti-itch lotion to bring with me on the trip, along with bringing an assortment of new first aid items to keep me sane. All that effort shaving grams off our bike, and now I was about to be a roaming pharmacy!

On Thursday morning before the race, we packed up our car and drove from Seattle to Astoria. Since my mom was in town to watch our cats during the race, she would be the one to drive our car back home after the event started. We settled down at the Comfort Inn, where I spent most of the next two days in bed.

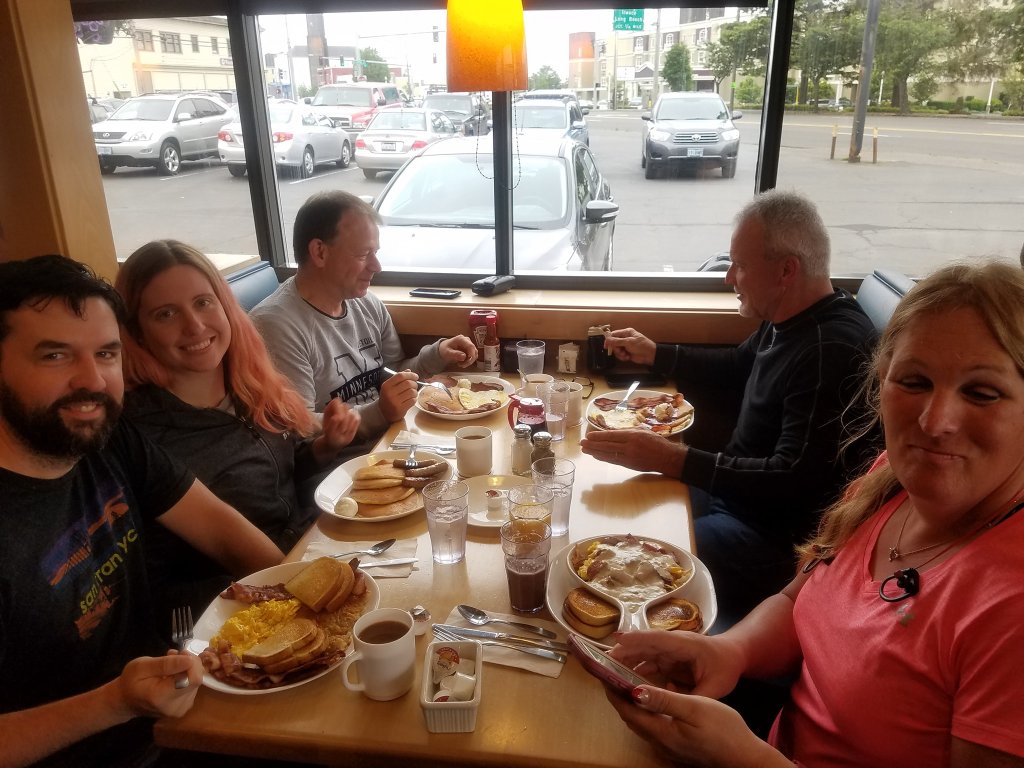

We did, however, make it out to the racer gathering at a brewery on Friday evening and to the Pig ‘N Pancake for breakfast the next day. I had to work up a lot of energy to get through those gatherings and it was very difficult to act ‘normal’ during them.

The pre-race inspection and meeting on Saturday night was quite bittersweet. I was so happy that we had made it this far, but time was up. I also felt INCREDIBLY sick during it. Despite pouring all my energy into preparing for this event, I had failed to figure out my health issues before the race started. I couldn’t help but feel that I had been robbed, and that this whole thing was a nightmare. I was so sad sitting there listening to Nathan, the race director, talking to us about the course, knowing that I was SO CLOSE to achieving my dream but yet so far at the same time.

Later on I laid in bed wide awake, tossing and turning and feeling worse than ever.